Anglo

Saxon Church, Bradford on Avon

I.

As regards its discovery, it may be stated, that until about the year 1856 no

suspicion existed as to there being a perfect church of its character and date

in England. Hemmed in on every side by buildings of one kind or another, on the

north by a large shed employed for the purposes of the neighbouring woollen manufactory;

on the south by a coach-house and stables which hid the south side of the chancel,

and by a modern house built against the same side of the nave; on the east by

what was formerly, as Leland tells us, “a very fair house of the building

of one Horton, a riche clothier,” the western gable of which was within a

very few feet of it, and hid it completely from the general view; - the design

and nature of the building entirely escaped the notice of archæologists.

The fact, moreover, of the west front being to a great extent modern work of the

seventeeth or eighteenth century, in feeble imitation of the old Romanesque, the

fragments of the original arcading now visible being then concealed by ivy which

has been since removed, thoroughly deceived casual observers, and indeed rendered

all at the first more or less sceptical in admitting the antiquity of the building.Although

it was known that an early church and monastery were founded in Bradford by St.

Aldhelm, yet the currently received opinion, which was repeated by one topographical

writer after another, that they had been utterly destroyed during the Danish wars,

encouraged no hopes whatever of our finding any traces of the original structure.

Nevertheless a conclusion had been arrived at, from the discovery of stone coffins

and traces of interment in the ground immediately adjoining the buildings in question,

that its site must have been on or about the same spot.

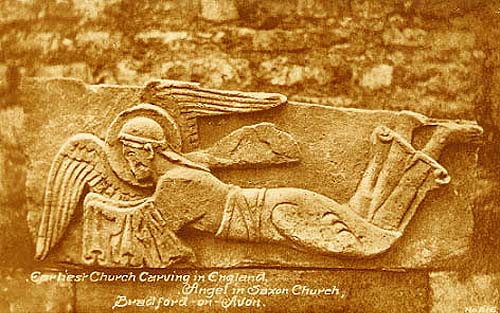

It was about twenty

years ago that, during the progress of some repairs, amongst which was the enlargement

of a chimney flue that ran up at the east end of what was then a schoolroom and

has since turned out, little as we then suspected it, to have been the east wall

of the original nave of the Church, two very ancient stone figures of angels were

discovered.* They were found imbedded in the wall, one on either side. They were

removed, one of them necessarily, for the insertion of the flue, and for some

time were placed over the porch leading to the modern house attached to the building

on the south side. I had no opportunity of inspecting the portion of the wall

from which they were taken, for the plaster ceiling of the schoolroom, which had

been partially removed for the purpose of constructing the flue, was at once replaced.

But the sculptured angels presented so strong a resemblance to figures found in

the Utrecht Psalter of the ninth century, and in the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold,

a manuscript (See Arcæologia, xxiv., plate viii) of the tenth century, as

to set one thinking that they must have formed part of an ancient structure, even

though they were all that remained of it.

Time went on, and it was determined

that the annual meeting of the Wiltshire Archælogical Society should be

held at Bradford-on-Avon in 1857. A request was made that I would prepare a short

history of the parish. Whilst collecting materials for this paper, I visited,

together with a worthy parishioner, to whose family it had once belonged, an ancient

chapel then in ruins – the Chapel of St Mary, Tory- situated at the very

highest point of the hill that closes in our town on the north side. After examining

carefully all the remains on the spot, we looked from the height on the town that

lay beneath us. And it was then that the truth first flashed on my mind that,

after all, there might be some remains of our ancient Church or Monastery; for,

looking at a block of buildings on its presumed site, my eye was attracted by

three lines of roof, slightly higher than the rest, which seemed to indicate the

outline of the Nave-Chancel-and Porch, or, it might be, transept, of an ancient

church. My friend was sceptical, but we came down the hill together and examined,

as far as we could, the structure thus indicated. But it was so buried in the

superincumbent earth, and so completely hidden by what have been not unhappily

termed “parasitic buildings,” and withal so difficult of access, that

our investigation was by no means a satisfactory one. Still the impression never

left me, that here at least we should find some fragments of our ancient Church,

and that in the old arcading, small portions of, which were visible on closer

examination, we had, it might be, a part of the original structure.

In August

1857, the Wiltshire Archæological Society held its meeting at Bradford-on-Avon.

In a paper read before its members attention was called to this building, but

it was hardly possible even for a practised eye to trace out its design, and few,

if any, seemed willing to believe it to be a genuine relic of bygone ages. It

is right however to add that a heavy storm of rain prevented any careful observation

of it on that occasion.

About a year afterwards an account of the building

was published in the magazine of the Wilts Archaælogical Society (vol. v.

247). It was illustrated by a set of drawings, showing the ground plan and elevations,

made by the Rev. W. C. Lukis, then one of the secretaries of the Society, who

felt an especial interest in the work from having been at a previous period for

some years curate of the parish.

Though not a few men of mark well able to

form a judgment on the matter, amongst them Mr. E. A. Freeman, Sir Gilbert Scott,

and Mr. Petit, pronounced for the extreme antiquity of this building, yet it must

be confessed that its genuineness, as a portion at least of the foundation of

St. Aldhelm, was by no means generally accepted. To find a stone building of this

date and character was so opposed to the theories, concerning what is commonly

termed Saxon architecture, that had been promulgated and received, that it is

hardly to be wondered at, that men generally were more or less sceptical upon

the subject.

A most important link however in documentary evidence came unexpectedly

to our help. In the year 1871 I was sitting in the Bodleian Library at Oxford,

searching for materials on other subjects, when I saw for the first time, among

the volumes published under the direction of the Master of the Rolls, one recently

issued, viz., William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Pontificum. At p. 346 of that

volume I lighted on this passage: “Et est ad hunc diem eo loci (sc Bradeford)

ECCLESIOLA quam ad nomen beatissimi Laurentii fecisse predicatur Aldhelmus:”

– that is, “To this day there is at that place (Bradeford) a little

church which Aldhelm is said to have founded and dedicated to the blessed St.

Laurence.” William of Malmesbury wrote this at latest about 1120, and here

avows his distinct belief not only that our ecclesiola was even then an ancient

building, but the work of St. Aldhelm, who died A.D. 709. I felt now that I had

found a key which unlocked the door of many of our difficulties, and with more

boldness challenged acceptance for our views. And it was indeed a help to us when

an article in the Saturday Review (October 19th, 1872), written by one who is

well able to pronounce authoritatively on such matters, thus summed up the arguments

in favour of our theory: -“We know that William of Malmesbury believed this

church to have been built by Aldhelm, and that we have no other historical statement

which either confirms or contradicts his belief. And is his belief so incredible

as to be set aside on a priori grounds? For our own part we see no difficulty

whatever in believing as William did. We see no objection to his belief, except

the vague notion that Aldhelm, at the end of the seventh century, or beginning

of the eighth, could not have built anything. But this is simply the dream of

people to whom all old English history is a blank, who fancy that all ‘the

Saxons’ lived at one time, and who sometimes argue as if Beda’s account

of the rudeness of Scottish buildings in the seventh century proved something

about English buildings three or four hundred years afterwards. The masonry is

certainly smoother than most early Romanesque work, but Wilfrith had already built

at Ripon ex polito lapide. In fact, as we see the matter, we have William of Malmesbury’s

statement on the one hand; we have a mere superstition on the other. We have very

little doubt as to which of the two we should choose.”

From that time

we may fairly say that the authenticity of our “little church” has been

generally acknowledged. In the last edition of Rickman on Architecture, a short

account, together with an illustrative drawing, is given of it. Moreover, the

contributions of the Society of Antiquaries, as well as of the Wiltshire, and

several of the local archælogical associations, towards the fund for its

purchase and conservation, are valuable testimonies to their belief of its being

a genuine relic of the early days of Christianity in Wessex.

II. And now as

to the history, as far as we know it, of this ecclesiola. The great interest attaching

to this building consists of its being connected so intimately with the history

of St. Aldhelm, one of the holiest and most famous men in our early history. He

was of royal lineage, being as the chroniclers tell us, the son of Kenten, a name

conjectured by Mr. E. A. Freeman to be a form of Centwin, the king who preceded

Ine in the throne of Wessex. If so, and the conjecture seems probable enough,

Aldhelm comes before us as one who for the sake of God renounced all claim to

the crown of Wessex, his saintship hindering him from becoming king. He was educated

at Malmesbury, and became ultimately head of the religious house that was established

there. Very diligent was he in his efforts to promulgate the truth among the semi-christianised,

if not to a great extent heathern, west-Saxons.

To this end he seems to have

been a great builder of churches. At Malmesbury he is said to have built two churches,

one within the monastery for the use of its inmates, and the other without its

walls, for the townsfolk or villagers. Moreover, he built a church near his own

private estate, “not far from Wareham, in Dorset, where Corfe Castle stands

out in the sea,” the remains of which were still to be seen in the days of

William of Malmesbury. He is said also to have founded a church at Briwetune (Bruton)

in Somerset. In truth the realm of Ine was adorned with a number of churches,

the work of his saintly kinsman.

In addition to these good works Aldhelm founded

two smaller monasteries and two churches also, at Frome and Bradford-on-Avon respectively.

As he became Abbot of Malmesbury about the year 670 and these “monasteries”

are alluded to in a deed of 705, [Codex Diplom., i., No. 54] the year in which

he became Bishop of Sherborn, their date would be towards the end of the seventh

century. By a smaller “monastery,” such as each of these was, is meant,

it may be as well to explain, a missionary settlement or centre from which the

blessings of Christianity were conveyed to the surrounding population. Indeed,

the word “monastery,” for some centuries after the time of which we

are writing, frequently meant only a church and dwelling-house, with three or

four priests, one might almost say missionaries, attached to it.

Such no doubt

was the character of the “monastery,” which Aldhelm established at Bradford-on-Avon.

As we have seen, William of Malmesbury, writing four hundred years at least after

its erection, speaks of the ecclesiola as still standing. And now, twelve hundred

years since Aldhelm lived, we still have this ecclesiola preserved to us, a most

precious relic of bygone days, still standing as it was first raised by its founder,

on the site of his uncle Cenwalch’s victory at Bradford “by the Avon,”

telling its tale that the English of the seventh and eighth centuries, though

no doubt they usually built their simple churches of wood, were nevertheless quite

able, especially when materials were close at hand, to build them also in stone.

The

monastery at Bradford-on-Avon would seem to have been regarded as subordinate

to the large religious house at Malmesbury, and its inmates always, until his

death in 709, looked up to Aldhelm as their superior. The diocese of Sherborne,

which was constituted in 705, contained all “west of Selwood;” and so

included, no doubt, not only Somerset and Dorset, but much of the western portion

of Wilts: hence Malmesbury and Bradford-on-Avon were comprised in it. It does

not appear however that the smaller monastery here was supported by means derived

from Malmesbury, or that the monastery at Malmesbury had estates in Bradford or

its immediate vicinity. The monastery and church of St. Laurence here owed allegiance

to Malmesbury and its Abbot, but otherwise seem to have been an independent foundation.

After

Aldhelm’s decease in 709 we do not meet with any notice whatever of our ecclesiola,

or monastery, in connection with Malmesbury; but after a lapse of three hundred

years we find them in the hands of the King of Wessex, for in the year 1001 King

Æthelred bestowed the monastery (cenobium) , with the adjacent vill or manor

(cum undique adjacente willa), on the Abbess of Shaftesbury. The specific object

of this gift is declared to be the “providing the nuns a safe refuge”

(the exact words of the charter are impenetrabile confugium) from the attacks

of the Danes, and a hiding-place for the relics of the blessed King Edward, then

recently martyred, and the rest of the saints. Æthelred further directs

that, on the restoration of peace in his kingdom, the nuns should return to their

ancient place; but that some of the society, if such should be the wish of the

superior for the time being, should always remain at Bradford. Without doubt in

those early days the large forests which were on every side of Bradford rendered

it a secure hiding-place (impenetrabile confugium), and difficult of access to

any large armed force. [Codex Diplom., iii., No. 706]

For more than five hundred

years the church and manor of Bradford, included in which was our ecclesiola,

were in the hands of the Abbess of Shaftesbury. At the time of the dissolution

of monasteries all the property again became the possession of the crown. All

that apppertained to the church or rectory of Bradford was granted in 34 Henry

VIII. (1543) to the Dean and Chapter of Bristol. What may be termed the lay manor,

of which our little church and its surroundings formed part, would seem to have

been the subject of several terminable grants; but at last it was granted in fee

to Sir Francis Walsingham, who however did not come into actual possession of

the same till 1588. On his decease in 1590, the manor of Bradford descended to

his daughter, who had some years previously married the Earl of Clanricarde.

Various

members of the Yerbury and Methuen families seem, from entries in surveys of the

manor, to have held our “little chapel,” and certain houses and lands

annexed to it, as copyholders under the lord of the manor for the time being.

In the year 1712 it was in the hands of Mr Anthony Methuen. At that time the Rev.

John Rogers, the vicar of the parish, opened a school for his poorer parishioners;

and three years afterwards Mr Anthony Methuen, as lessee, with the consent of

the then lord of the manor, granted what was really the nave and porch of our

ecclesiola as a “charity schoolhouse;” the chancel being still reserved,

and then or previously separated from the rest of the building by destroying the

chancel-arch, and then walling up the opening and inserting large chimney-flues.

The use to which it had been previously devoted is told us in the deed by which

it was conveyed to certain trustees. It is there described as a “building

adjoining to the churchyard in Bradford, commonly called or known by the name

of the Skull House,” from the fact, most probably, of its having been used

as a charnel-house. The chancel remained as part of the copyhold described above,

and was occupied as a gardener’s cottage. The property was subsequently enfranchised,

and became the possession in turn of members of the Methuen, Bethel, Bush and

Edmonds families. From one of the last named the Chancel was purchased early in

1872, for the purpose of securing, at all events, a portion of so unique a church

from future desecration or injury.

The negotiations for securing the Nave were

somewhat intricate. As it belonged, together with the house built up against its

south side, to the Trustees of the Charity School, it could not be sold without

the consent of the Charity Commissioners, who stipulated that the interests of

the school must be fully preserved. At last another large building, itself of

some historic interest, the “Old Church House,” built, as Leland tell

us, in the fifteenth century by one of the Horton family, was purchased, and,

with their permission, accepted in exchange by the Trustees of the Charity School

for the nave and porch, which they had held for some hundred and fifty years.

So

bit by bit this precious relic of the past was recovered. Though funds hardly

sufficed for the outlay, it was found absolutely necessary, as soon as possession

was obtained, to restore the chancel-arch, the window, and arcading at the south-east

corner of the Nave, as well as the two arched doorways in the centre, respectively,

of the north and south side of the Nave. Fortunately, in removing the large chimney-stacks,

and in excavating the floor, many of the original stones, both of the chancel-arch

and of other portions of the building, which had been mutilated, were discovered,

and these have been faithfully replaced in their original position.

III. We

now proceed to discuss the architectural features of this “little church”

[I am indebted for valuable assistance, in drawing up this account of the architectural

features of the “little church,” to Mr. C. E.I. Davis, F.S.A., of Bath].

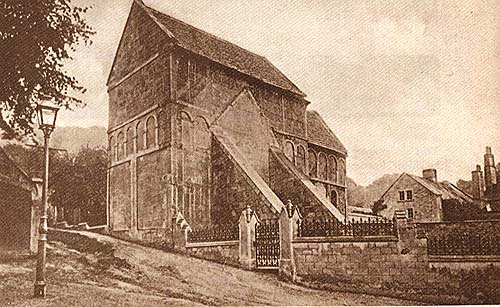

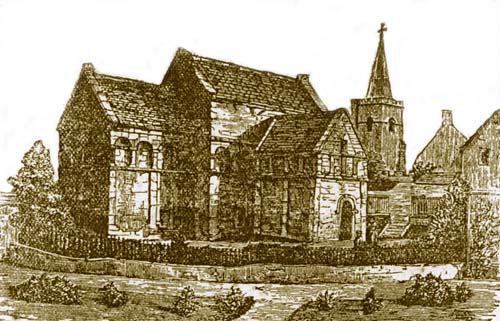

As

it stands at present it consists of a NAVE, a CHANCEL, and a PORCH on the north

side. Originally however the building was cruciform, there having been a building

similar in form and proportions to the porch on the north side; for not only can

the foundations be traced, but, the plaster having been cleared away, we can distinctly

trace, not only the place where the wall that was at the west side has been removed,

but also the line of the roof. Moreover, the eastern wall is in fact standing,

and forms a portion of the wall of the house, which, judging from its style, was

erected about 300 years ago against the south side of the nave. There can be little

doubt that this southern annexe- it can hardly be called a transept – contained

rooms for the priests attached to this ecclesiola or for the sacristan who was

entrusted with the care of the building. That this was a dwelling-house rather

than a porch is clear from the fact that, whilst the doorway on the north side

is ornamented, there is nothing to be seen on the doorway on the south side, showing

that the former at all events was the public entrance to the little church.

The

internal dimensions of the several portions are as follows: - Nave E to W 25ft.

2in. N. to S. 13ft., 2in.; Chancel E to W 13ft. 2in., N to s. 10ft., 0in; Porch

9ft. 11in., N to S 10ft. 5in. (DRAWING)

One characteristic feature of the building,

when compared with its area, is its great height, which looks to modern eyes so

strangely disproportionate to its other dimensions, and reminds us strikingly

of the rude drawings of churches which we find in ancient manuscripts of the tenth

and following centuries. This is remarkably the case in the illustrations found

in the Benedictional of St Æthelwold, and in the representation of the church

at Bosham, (so intimately connected with the history and fortunes of Harold),

as it is given the Bayeux tapestry. Thus, from the ground-line to the wall plate,

the nave is 25ft 5in.; - the chancel 18ft. 4in.; - and the porch 15ft. 6in.

All

the elevations except that of the porch were divided into three stages. The lowest

was quite plain, with the exception only of a series of slight projections not

inserted, but cut out of the stone, and which are really so slight that they can

only be called pilasters, and not buttresses. These occur at regular intervals

and support a string-course which ran all round the building. These pilasters

have in several places “stepped bases,” such as are commonly seen in

drawings found in manuscripts of the tenth and eleventh century. Upon the string-course

runs an arcade, consisting of a series of flat pilasters, consisting of upright

stones, which however do not tail into the wall, and which, on the east (thus

distinguishing the chancel from the rest of the building), are partially moulded.

All these have bases and caps, cut out from the surface of square blocks of stone,

and most of them are slightly bevelled on either side. These latter support, or

rather appear to support, a series of plain arches; for the arches themselves

are only surface decorations, and not at all constructive arches, being, like

the pilasters, caps and bases, all cut out of the stone, which runs, irrespectively

of them, in regular courses. In fact the walls seem to have been built at first

plain, with the bands or string-courses alone projecting, the panels and ornamentation

being afterwards formed in them. The workmanship is of a very rude description;

in some cases these sham arches, as we may call them, are cut out of the surface

both above and below, in other cases only below. Elsewhere the work of “cutting

out” seems to have been only partially completed. Moreover, the elevations

of the arches are by no means strictly uniform, the arch on the south side of

the eastern elevation being several inches higher than the rest. In truth the

walls themselves are of different thicknesses in different parts of the building.

Around the Porch, the pilasters, of which we have spoken, do not support arches

at all, but merely a tabling which is built to receive the eaves.

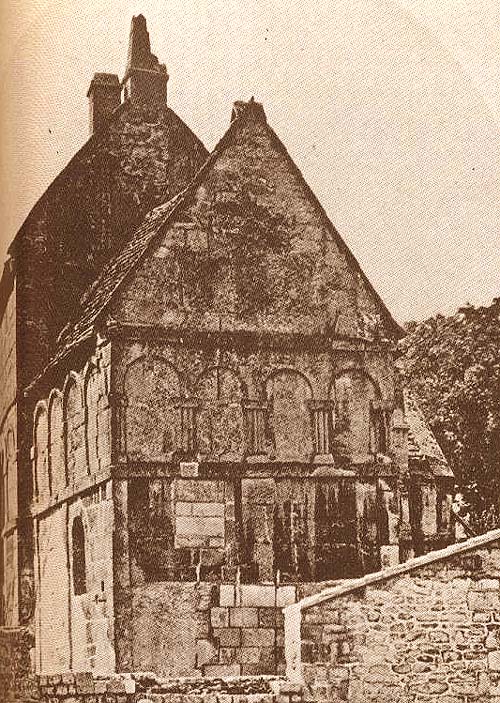

In the eastern

gable of the Nave are the remains of several moulded pilasters, which formed a

sort of arcade built to take the form of the pitch of the rook, being stilted

in increasing height to the centre. Above the tabling on the north side of the

Porch there would seem to have been a similar arrangement, the centre pilaster,

or rather the greater portion of it, which is rudely moulded, yet remaining.

THE

CHANCEL is entered through an archway which is only three feet five inches wide.

The arch springs from an impost, and has the usual characteristics of ante-Norman

work.. A large portion of the outer arch was found either in the chimney which

was removed or under the floor, and has been replaced in its original position.

Its disproportion in size to the height of the wall is very striking. Above this

arch, imbedded in the wall, were found, during the progress of some alterations

about eighteen years ago, two stone figures of angels, one on either side.

These

figures, which may fairly be deemed co-eval with the building itself, are executed

in a kind of low relief. The angels have their wings expanded, around their heads

is the nimbus, and over an arm each holds what is conjectured to represent a napkin.

They have now been replaced in the position in which they were found. It is conceived

that originally there was a central figure of our blessed Lord upon the cross.

There is to be seen still in the curious, though sadly mutilated, sculpture in

the church of Headbourne Worthy. [See a drawing of this Church, showing this rood

with the two attendant figures of St. Mary and St. John, in the Journal of the

Archæolog. Assoc. (Winchester Volume) p. 412], near Winchester (a building

the principal portion of which is of the date of the tenth century), a design

which seems to warrant such a conjecture. The whole group might thus symbolise

the deep and reverent care that the blessed angels have for all that is connected

with “the sufferings of Christ and the glory that should follow,” as

St. Peter expresses it – “which things the angels desire to look into.”

– 1 Peter i. 12.

The pilasters on the east elevation of the Chancel are

moulded into three depressed roundels, a very simple form of decoration –

one of the earliest in fact met with in this country. This work is especially

valuable, as it seems clearly to denote, in the mind of the builder, the superiority

of the eastern over the western elevation, and so to mark the building as a Christian

Church. Moreover, when considered together with the peculiar way in which the

lesser pilasters below the arcade are formed, it seems to mark out very distinctly

the antiquity of the structure.

There is a window still remaining in the south

wall of the Chancel. It is splayed considerably both inside and outside. Though

it may, judging from the fact that it is constructed of separate stones and has

some very slight Norman characteristics, possibly be a later insertion, yet there

are those, whose opinion must carry weight, that consider it as one of the original

windows.

Among minor peculiarities may be observed the step down into the Chancel,

and also the incisions just below the impost of the Chancel arch, into which it

is supposed were driven the blocks of wood in which were the iron staples on which

the Chancel gates hung.

The Nave is entered from the north Porch by an archway,

which was sadly mutilated, but has now been restored. The archway, is two feet

ten inches wide, and eight feet six inches high to the centre of the arch. It

springs from an impost, which is itself simply a plain string-course, stopping

a slightly moulded pilaster formed by a series of segmental roundels. Above the

impost this is continued over the arch as a hood-moulding. This arch is certainly

one of the earliest enriched or ornamented yet known. It may be remarked that

the opening of this door-way is wider at the floor than at the springing –

one of those minor peculiarities which tend to confirm our statements as to its

antiquity.

In the western wall of the Nave the original arcade, which ran round

the entire building, has been much mutilated, for the purpose of inserting modern

windows. One of the old estones of the arcade is still to be seen, the semicircular

arch which was at the first cut out of the stone having been subsequently chiselled

off and the stone used for filling up a portion of the wall above the more recent

openings. In the south wall of the Nave there is a window.

The

Porch is on the north side of the building and would seem originally to have had

on its front a series of moulded pilasters, like those on the eastern gable of

the Nave already described, above the plain arcade, the larger portion of the

central one still remaining. It was entered by a door-way, which, though simpler

in its details, corresponds in its general characteristics with the entrance to

the Nave, of which an account has just been give. As another instance of the rudeness

of the construction of the buildings it may be mentioned that the porch is longer

by several inches on the east than on the west side.

Such

is the “little church,” which, after centuries of desecration, has been

recovered and once more devoted to those holy uses for which it was at first erected.

To an archaæologist this unique building must ever be one of the deepest

interest. To a Christian also it ought to be precious, for it is without doubt

“the place by the river side where prayer was wont to be made” more

than a thousand years ago, when, and even before, Alfred the Great ruled in Wessex.

It is a relic in fact of the early Christianity of our forefathers in this part

of the country, telling of the self-denying labours of the holy Aldhelm, than

whom no one in his time did more in propagating the truth among his countrymen,

and who laid not down his pastoral staff, till with it he laid down his life in

his Master’s service.

The

“little church” for some time past has been used for daily prayer, and

for occasional services such as devotional meetings preparatory to Holy Communion,

addresses, and services for the benefit of candidates for confirmation. In a room

in the house erected on the south side of the church, and which Sir Gilbert Scott

thought it not only unsafe but undesirable to remove, inasmuch as it would render

necessary the reconstruction of the whole of the south side of the Church and

so virtually destroy its identity, are held Bible Classes, meetings of District

Visitors, or of the members of a Girls’ Friendly Society. In fact the room

is a “Church room,” available for any good purposes in connection with

the parish. It is hoped that in this way the provisions of the Trust Deed are

fully and faithfully carried out, which direct that the Trusteees (of whom there

are seven) “shall keep and preserve the church as a memorial of past ages,

and for public benefit and instruction, with a due regard always to the object

for which the said church was originally erected, namely, as a place dedicated

to the worship and service of Almighty God.” [A copy of the Trust Deed was

printed in the Wiltshire Archæological Magazine, Vol. xvi. p. 346.]

One

concluding remark shall be made with reference to this “little church.”

This shall be given in the words of Mr. E. A. Freeman, from a paper read by him

before the Somerset Archæological Society in 1874.- “Without all doubt

this building of Aldhelm’s, which remains to us, is a type of those larger

churches, all of which have perished, that he erected elsewhere. We must picture

to ourselves the Abbey Church at Malmesbury, and the Cathedral Church at Sherborne,

as they came from the hands of Aldhelm, as buildings presenting what we may suppose

to have been the likeness of a greater Bradford.”… “The time of

King Ine was one of remarkable activity in the way of church building. With Aldhelm

in the south, with Wilfrith and Benedict Biscop in the north, churches were rising

in many places. And our West-Saxon Bradford, the work of Aldhelm, during the reign

of King Ine, may fairly be set against the two famous churches of the north, the

churches of Benedict, at Jarrow and Monkweamouth. If we have but one church to

set against two we may say that Bradford is all but perfect whilst Jarrow, and

Monkweamouth have been largely altered in later though still in ancient times.

In mere workmanship Bradford altogether surpasses the contemporary parts of the

Northumbrian buildings. And, as for their personal memories, if we must yield

the first place among the native worthies of the early English Church to Northumbrian

Bæda, we may fairly claim a place, only second to his, for West-Saxon Aldhelm.