King Charles II visit to Charmouth in 1651

I have been fascinated by the gentleman who planned and nearly succeeded in the attempt to assist King CharlesII in his Escape to France. His name was William Ellesdon and both he and his descendants were to dominate the lives of villagers for nearly 150 years. I have tried to build up a picture of Charmouth during this turbulent chapter in the country's history from the limited records that have survived. The year before the Civil war began in 1641, Parliament decreed that all males over 18 should take a Protestation ( declaration of loyalty) Oath . All names were listed and anyone who refused to take it was recorded. Seventy five gentleman were to sign it in Charmouth, which has shown to equate to an approximate total population of 250. In the same year there was an order that the hundred of Whitchurch and the tithings of Hawkchurch and Dalwood were ordered to contribute £ 10 per year to the Poor Rates of Charmouth -"where there are many poor people whom the parish cannot relieve".

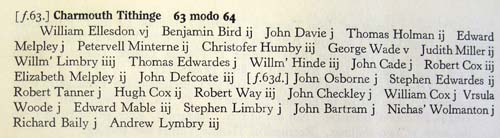

A further insight into the state of the village can be seen in the comprehensive survey carried out by Sir William Petre when he purchased it from the Queen a century before . The original document survives in Devon Record Office and clearly shows that the majority of his tenants occupied cottages along the Street with an acre of land and a further acre of common land which they farmed.There were a number of people who had larger holdings, the most prominent of whom were the Limbrys. A branch of this family lived in what is today' s Charmouth House, but then known as The Fountain. It was one of a number of hostelries along the Street that served travellers using the London to Exeter road that passed through the village. A descendant of this family, Stephen Limbry was to feature as the seaman in the attempted escape of King Charles II. A contemporary road map by John Ogilby shows the village with its main Street lined with houses and the paths to the sea, now Lower Sea Lane and Barr ' s Lane which led to Wootton Fitzpaine.

At the beginning of the Civil War the village was mainly owned by Sir John Pole. He had sided with Parliament and in 1643 he twice helped to lead anti-royalist raids in Devon and Cornwall. However, he also participated in abortive local peace negotiations that year . His position in Devon was complicated by his son William ' s decision to fight for the king, and both Colcombe Castle and Shute Barton were badly damaged during the war, by royalist and parliamentarian forces respectively. He was active in local government but he evidently disapproved of Charles I ' s execution as he declined to serve under the Commonwealth, despite being retained on the Devon bench. He died in April 1658, and was buried at Colyton, where he had erected a lavish monument to himself and his first wife. Although he was to sell the Manor of Charmouth to William Ellesdon in 1648, he retained The Mill and 35 acres of land in the village, which was eventually to be sold by his descendants at the the end of the 18th. Century.

William Ellesdon in contrast to Sir John Pole was a staunch Royalist. No doubt his father,Anthony held the same sympathies and in buying the adjoining Newlands with its fine house, Stonebarrow Manor, the following year was making a hasty departure from Lyme Regis,where he had been Mayor no less than three times. This town had always held an independent stance and was known as a Parliamentarian strong hold. This culminated in the famous Siege of 1644,when for 8 weeks they withstood the forces of Prince Maurice, who eventually abandoned his attempt.Loyalties to each side existed within families and it is interesting to see who William's brother, John supported, for there is a later letter from Col. Robert Mohun "setting forth articles against John Ellesden, who was put into the place of Collector of Customs of Lyme by Cromwell".

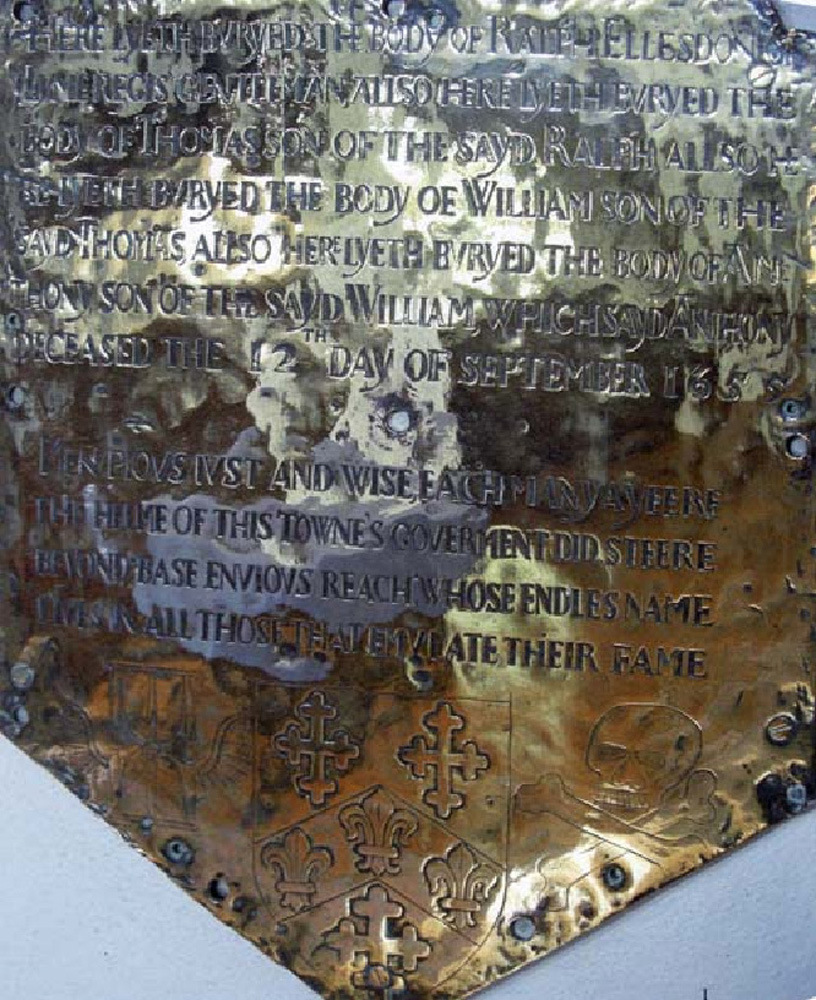

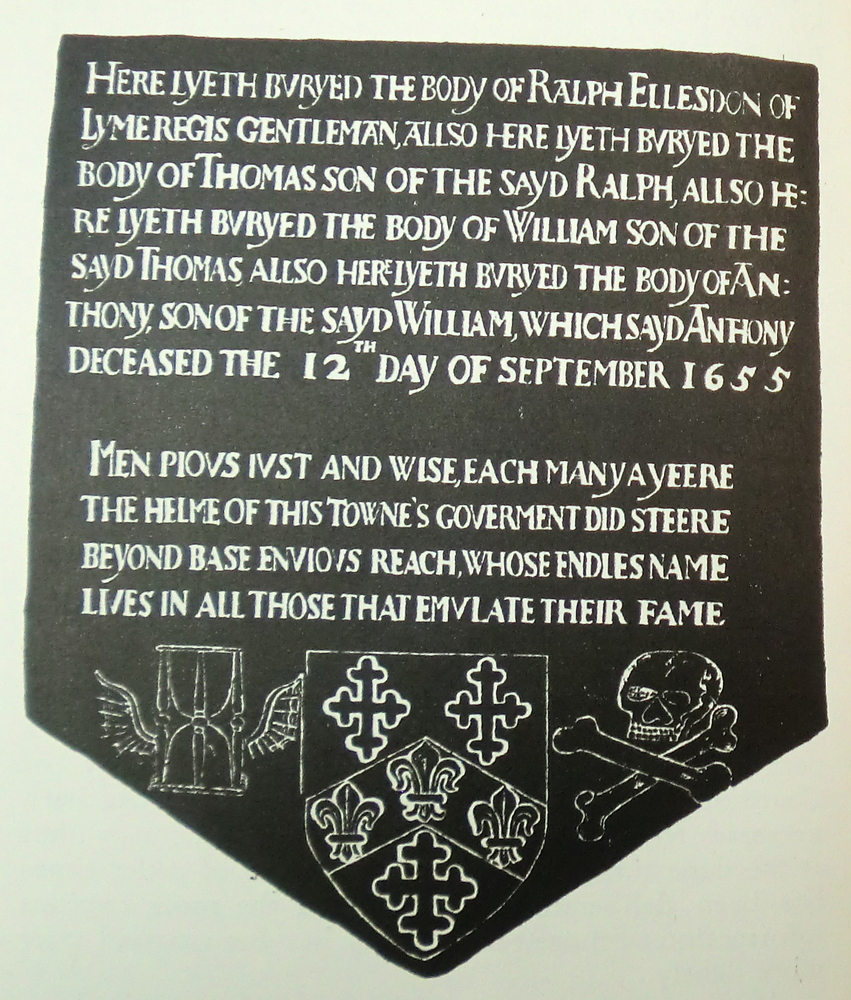

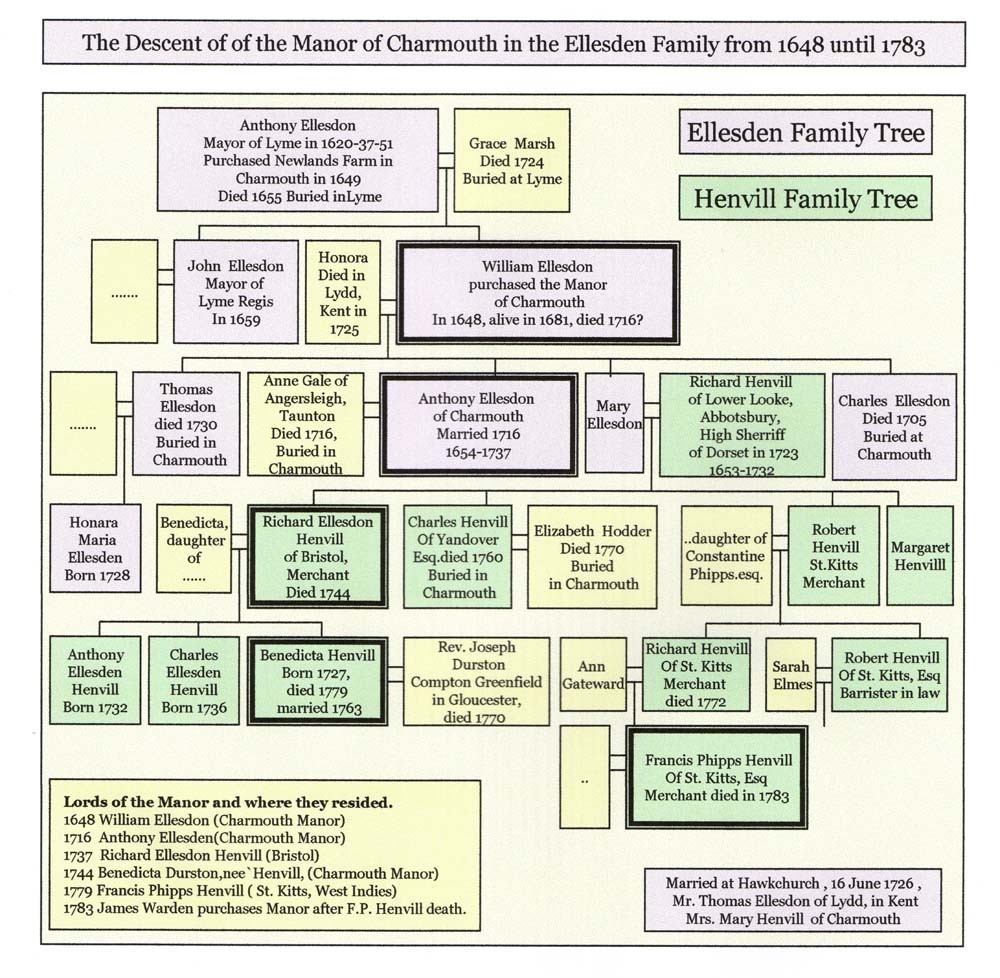

The Ellesdons were originally successful merchants from Lyme Regis and were regularly Mayors of the borough. The Church still has a brass shield which extols them and records 4 generation being buried in their vault. Coincidentally the last is Anthony, father of William Ellesdon the central character to this article who is shown as dying in 1655. This same gentleman purchased the Manor of Newlands, which today forms part of Charmouth in 1649. The family lived in a large house in Church Street,near where the famous George Inn stood. It was here that William and his brother John were to be bought up by their parents Grace and Anthony. Johns life was to be spent in Lyme Regis where he was to eventually become it's Mayor in 1659 and with his wife Sarah Clapcott have four children,John,Grace,Mary, Thomas. The latter was to briefly unite the two branches of the family by marrying his cousin Mary in 1726, who by then was a widow on the death of her husband, Richard Henvill.

William Ellesdon was a Royalist and held the position of Captain and later Colonel in the army and was to risk his life in support of the King. For that would have been his fate if charged for assisting in his escape. It must have been a miracle that he was able to remain a free man until his return.He had been earlier successful in assisting Lord Berkley escape across to France after the Battle of Worcester and no doubt would have repeated this with Charles, if Stephen Limbry had not returned home to his angry wife. But King Charles was to give him a gold coin when he briefly spent the night before the planned escape at a house his father owned at Monkton Wyld, still called Elsdons. At the same time he promised that when he regained his throne he would reward him handsomely.His Majesty, on his restoration visited the village and granted to him and two successive heirs a pension of £ 300 per annum, and presented him with a medal bearing the inscription "Faithful to the Horns of the Altar". The King also gives a beautiful miniature by Samuel Cooper of Ellesdon , together with a pair of silver candlesticks. He was also presented with a coat of arms, which can be seen today on their marble memorial in St. Andrews and on a large plaque commemorating his son's later improvements to the church.

The pension was for both him and his immediate family and would be derived from taxes received from the port of Lyme Regis. There is a website called british history online that has a huge database covering parliamentary records and almost yearly there are references to those benefitting from his pension and through this I have been able to obtain important information about the family. Most intriguing was £ 1000 he was to receive in 1663 for his work for the King's Secret Service. Unfortunately the money was often not forthcoming and there are pleas from his family for these outstanding payments. It shows that he died in 1684, the year before the Monmouth Rebellion, but his pension was to continue to be received by his wife, Joanne and children - Anthony, Charles, Mary and Anne. It was his eldest son Anthony who was to take over his role and live in what was the largest house in the village opposite the Church, where he lived for almost 80 years. Little is known about him apart from the charitable work that he did that is recorded on the impressive marble monument erected by his niece's husband, Richard Henvill who inherited his estate. He no doubt had the same loyalty as his father to King Charles II, as he was still receiving a pension of £ 100 a year as a result of his support.

KIng Charles II

The Oak Tree at Boscable

Escape

Trent

Elsdons Monkton Wylde

The plaque is one of a number in the area which were placed on building associated with the Escape of king Charles II in 1651.

Abbots House Hotel in the Street in Charmouth today

The plaque above the entrance doorway at Abbots House

The Royal Oak in Charmouth today with its hanging sign recording the Escape of Charles II

The hanging sign at the Royal Oak in Charmouth

A print showing king Charles after the restoration returning in glory.

William Ellesdon, Lord of the Manor of Charmouth must have been held in high regard by King Charles as he almost succeeded in assisting in the escape of King Charles II to France after the battle of Worcester. William had formerly been a Captain for the Royalists who had since become a successful Merchant. He had assisted in the escape of Lord Berkeley to France and it was for this reason that Colonel Wyndham recommended him to the King to assist in his escape.

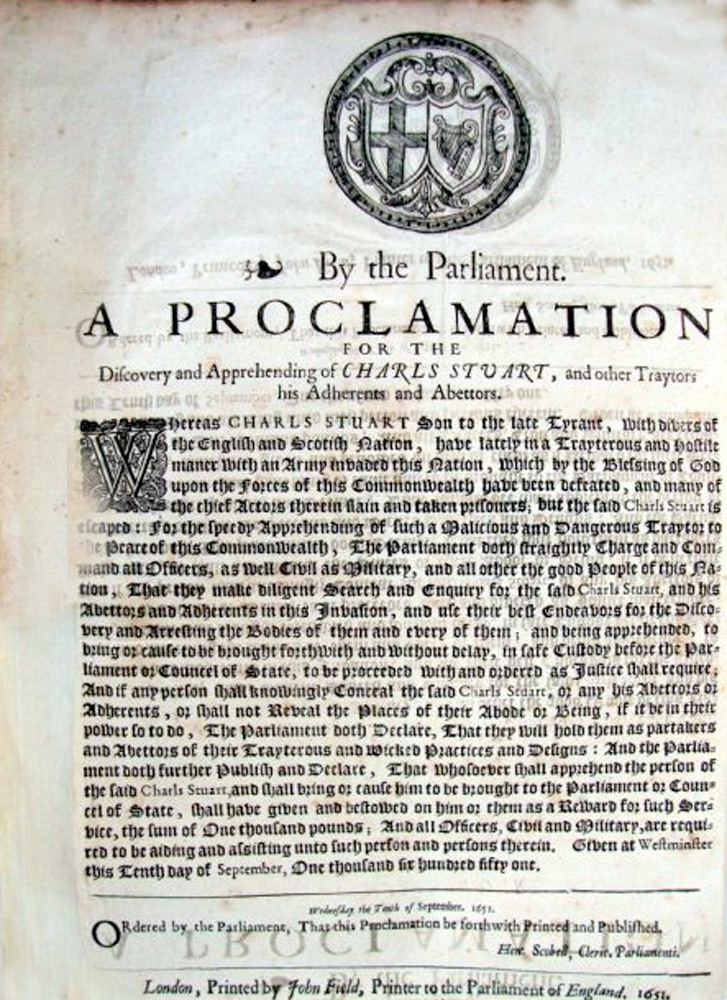

The King left his refuge at Trent, south of Dorchester and was to stay overnight with John, brother of William Ellesdon at his house at Monkton Wylde which still stands today and is known as Elsdon`s Farmhouse. He was then going on to Charmouth where a boat would be waiting to take him to France and safety. Unfortunately the scheme backfired when the wife of the boat man, Stephen Lymbry, found out and locked him in a room in their house. As a result the future king had to spend a night at what is now the "Abbots House" in the Street, before travelling on to Bridport. This event was to put Charmouth on the map forever more and our own William Ellesden in a long letter tells the story in vivid detail to Lord Clarendon of his part in the story, which is shown below.

In reward for Captain Ellesdon`s services and loyalty, his Majesty, on his restoration visited the village on July 2, 1671and granted to him and two successive heirs a pension of £300 per annum. He was presented with a medal bearing the inscription "faithful to the horns of the Altar". The King also gave him a beautiful miniature by Samuel Cooper, together with a pair of silver candlesticks, which are believed to be in the West Indies, when descendants settled there.

In the years 1681-3, the Mayor of Lyme Regis, Captain Gregory Alford, showed much energy in the persecution of Dissenters and accused William Ellesden of conniving in the proceedings of conventicle preachers. There is a letter dated February 18 th 1681 where Ellesden writes in his defence that: �He has no power in Lyme and is not a magistrate of the borough. He lives at Charmouth 11/2 miles away, but is willing to execute the laws under dissenters. He goes on to say that Captain Gregory Alford did read his letter to every person he did meet with in the street, to men, women & Children, by which means, having notice of it , did avoid the apprehension. He wishes for an order to arrest John Brice a conventicle preacher in Charmouth. He has no jurisdiction in Lyme�.

More than a year later William Ellesden was still living, for on July 7 1683, the Bishop of Bristol complains of his � discouraging the King`s information against unlawful Conventicle meetings, � allaging that � he refused to give to the poor of the parish, & gave always to every preacher that was convicted�. Ellesdon at that time was over 60. He was born in 1620 and purchased the Manor of Charmouth in 1648.He was no doubt still Lord of the Manor of Charmouth in 1685 when the Duke of Monmouth passed the shores of the village on his way to Lyme Regis. It is interesting to read that by 1689 his heirs petitioned the House of Commons for the payment of the arrears due of the pension granted him on account of the assistance he gave King Charles in 1651.

King Charles II had got safe to Trent, near Sherborne. The matter was to get him out of England, for his enemies were following every scent. One design had already come to nothing, when Colonel Wyndham, his Majesty's host, bethought him of a certain Captain William Ellesden of Lyme, who had had a hand in getting Sir John Berkeley over the sea. Wyndham went to Lyme, found Ellesden and told his story, taking the precaution, however, to name only Lord Wilmot as concerned in the adventure. Ellesden, a staunch loyalist, readily promised his aid. He brought the colonel to Charmouth to a tenant of his, Stephen Limbry, who agreed for a fee of sixty pounds to have a boat in readiness in Charmouth roads at a given date and to conduct the party, of whose names and rank he was, of course, ignorant, safely to France.

The preliminaries settled, Wyndham's next concern was to get the king to Charmouth, and also to provide that his midnight departure should not arouse suspicions. He sent his servant, Henry Peters, to the Queen's Arms; and Peters, over a glass of wine, told the landlady, a sentimental soul, a gallant story of how his master loved a lady of Devon, and she him again, how stern parents thwarted their desires, and of how the lovers had decided for an elopement. He then arranged that the best room in the inn should be theirs for the appointed evening, though they would not sleep there but leave in the small hours of the following morning.

The day came. Julia Coningsby, Lady Wyndham's niece, rode postillion behind the King. The Colonel accompanied them, while Lord Wilmot and the man Peters followed at some distance, as though unconnected. The King masqueraded as William Jackson. On the way they called at the house of Captain Ellesden's brother, where Charles made himself known to the captain and gave him a piece of gold " in which, in his solitary hours, he made a hole to put a ribbon in.

Then the party went on to Charmouth to wait for Limbry. They waited. A serious hitch had occurred in that well-intentioned seaman's plans. His wife, uninformed of his project, and suspicious of his secrecy, had locked him in his room, where she kept him until morning. Meanwhile the anxious Royalists had sent a message to Ellesden, who advised a prompt departure from Charmouth. So, thwarted once more, they rode on to Bridport.

Ellesden's advice was wise. Suspicion had been aroused in other breasts besides the flinty Mrs. Limbry's. The King's horse had needed shoeing and the smith, Hammet, a man who knew his trade, noticed that the beast had been shod in three separate shires, and that one of the three was Worcestershire, the county in all men's thoughts. The ostler at the Queen's Arms, already in a state of curiosity about these strange gentlemen who had kept their horses saddled all night, went off at once to Mr. Wesley, the minister. But the parson was praying, and prayed so long that the ostler could not wait for the "Amen." When Wesley was at last told the news, Charles and his friends were well on the Bridport road.

This Mr.Wesley, who was great grandfather of the founder of Methodism, was a dry man who loved not romance. He favoured the roundhead cause and would gladly have apprehended the fugitive king. It was in an ill and sarcastic temper that he walked into the Queen's Arms Inn that morning. " Why, how now, Margaret! " he greeted the landlady. " You are a maid of honour now." " What mean you by that, Mr. Parson? " quoth she." Why, Charles Stuart lay last night at your house, and kissed you at his departure; so that now you can't be but a maid of honour." Margaret fired up. " If I thought it was the King," she retorted, " I would think the better of my lips all the days of my life, and so you, Mr. Parson, get out of my house." So poor Mr. Wesley retired, but it was lucky for Mistress Margaret that those were not the days of the Bloody Assizes.

At Bridport Charles put up at the George. Here again he was all but discovered. The place was full of soldiers and servants. The King, himself acting in the latter capacity, must mingle with the crowd in the yard. An ostler greeted him with puzzled recognition, and but for that ready wit of the Stuart's it is probable that his disguise would have been pierced. Anyway, another move was thought advisable. So the party took a by-road to Broadwindsor, where once more they found themselves in an inn-parlour full of soldiers. Fate seemed fighting for the roundheads, but an unexpected ally appeared in the person of a young woman, in the excitement of whose sudden travail the strangers were forgotten. Their next move was back to Trent.

The Letter of William Ellesdon of Charmouth to the Earl of Clarendon concerning the adventures of Charles II in West Dorset on September 22, 23 and 24, 1651 (Transcribed from the Original Letter preserved in the Bodleian Library)

Humbly conceiving that a compleat and perfect narration of the many and great dangers, and the as many and signal deliverances which his sacred majesty met withal after that fatal rout at Worcester, until his majesty's happy arrival at the port of safety which Almighty God, his gracious and merciful preserver, had designed for him, cannot but be very acceptable to all good Christians and loyal hearts, as being a work so much conducing to the glory of God, and the honour and renown of our most dread sovereign, and withal observing too great a defectiveness in those narratives on the subject that I have hitherto seen, as to some of those eminent deliverances which God was pleased mercifully to vouchsafe his majesty in the west ; to the intent that, if God shall stir up the heart of any learned and able historian to give a full and true account of those remarkable passages of Providence to the world, I may contribute my mite to such a noble and desirable undertaking ; I have now (upon presumption of your lordship's favourable acceptance) taken upon me the boldness to present unto your lordship a brief account of those memorable passages in this kind, which myself (as having been agent in them) had the honour and the happiness to be acquainted with ; the which your lordship may be pleased to take as followeth. After that his majesty was disappointed of his hopes of embarking at Bristol (of which your lordship may inform yourself in that account which a person of quality hath given the world, in his book stiled The History of his Sacred Majesty Charles the Second, printed at London, anno 1660, page 125), his majesty desired to be brought some miles westward, to the house of a worthy gentleman, whom he knew to be a trusty friend ; and accordingly, his majesty being conveyed to the house of Colonel Francis Wyndham of Trent, in Somerset, advice was had about preparation of passage for his majesty in some western port. In prosecution of which, myself being looked upon as person that might be confided in, and in a capacity of serving his majesty in order to his transportation (having not long before been instrumental in getting safe passage for Sir John, now Lord Berkeley), upon or about the 18th of September 1651, the aforesaid honourable and truly loyal gentleman, Colonel Francis Wyndham, came to me at my house at Lyme (where I then lived, looking upon it as some protection to me in those times to live in that town), when, after some other discourse had, and an engagement to secresy passed betwixt us, he told me that the king had sent him to me, commanding me to procure him a vessel in order to his transportation into some part of France. Being overjoyed to hear that my sovereign was so near me (as the colonel had informed me he was), and even ravished with content that an opportunity of expressing the loyalty of my heart to his most excellent majesty, so unexpectedly presented itself, I answered that I would with the utmost hazard of my person, and whatsoever else was dear unto me (as knowing myself by all obligations, both sacred and civil, thereunto obliged), strenuously endeavour the execution of his majesty's both just and reasonable commands in this particular ; being verily persuaded, that either God would preserve me from, or else support me in and under any sufferings for so good a cause. Accordingly, I immediately sent one to the custom-house to make enquiry who had entered his vessel as bound for France. News was brought me that one Stephen Limbry of Charmouth had lately entered his bark, and intended a speedy voyage for St Malo. Not only myself, but also Colonel Wyndham was much affected with these tidings; I having told him that I had an interest in the master (he being my tenant), and that he had ever the repute of being well affected to his majesty. Upon these encouragements, we (resolving to lose no time) rode to Charmouth by the seaside, to confer with the master, which way I the rather made choice of, that in our passage there I might show the colonel what place I judged most convenient for his majesty to take boat in (in case we could work the master to a compliance), in order to his embarking; and, indeed, a more commodious place for such a design could hardly be found, it lying upon the shore a quarter of a mile from any house, and from any horse or footpath. The colonel being fully satisfied of the conveniency of the place, we rode into the town, and immediately sent for the master, who being very happily at home, presently repaired to us at the inn. Friendly salutations and some endearing compliments being premised (and a name that was nothis own being by me, in the hearing of the master, given to the colonel, in the way of disguise), I told him that the end of our sending for him was to procure passage for a friend of mine and this gentleman's, who had a finger in the pye at Worcester. The man being startled at this proposition (as apprehending more than ordinary danger in such an undertaking), we were necessitated to use many arguments for the removal of his fears, which we so happily managed, that in a little time we saw the effect of them by his chearful undertaking the business. Wherefore, an ample reward being engaged for on our part, he promised speedily to prepare his vessel, and hale her out of the cob the Monday following, and about midnight to send his boat to the place appointed for the taking in of the passenger, and then immediately to put off to sea (in case the winds were favourable). Thus far we were agreed ; and in all our discourse, there was no enquiry made by the master, nor any the least intimation given by us, who this passenger might be, whose quality we purposely concealed, lest the hopes of gaining £1000 (the promised reward of the highest treason) might prove a temptation too strong for the master to grapple with. Having thus far successfully proceeded in our business, we returned to Lyme. And the next day returning to his house at Trent with these hopeful tidings to his majesty. I bore him company part of his journey, and chose the land road from Lyme to Charmouth, that upon the top of a hill, situate in our way betwixt these two towns, upon a second view he might be the more perfectly acquainted with the way that leads from Charmouth to the place appointed for his majesty's taking boat ; it being judged most convenient, upon several accounts, that the colonel, and not myself, should be his majesty's conductor thither. Here calling to mind that on Monday (the day appointed for his majesty's embarking) a fair was to be held at Lyme, and withal doubting lest upon that account (through the nearness of the place), our inn in Charmouth might be filled with other guests, we sent down one Harry Peters, then a servant of the colonel's (who yet was not with us the day before), with instructions, by an earnest of five shillings to secure the two best rooms in the inn against his majesty's coming ; who told the hostess (to take off suspicion) this fair tale : That there was a young man to come thither the next Monday, that had stolen a gentlewoman to marry her, and (fearing lest they should be followed and hindered) that he desired to have the house and stables at liberty to depart at whatsoever hour of the night he should think fittest. This message being performed, the rooms made sure of, and the servant returned, I then showed the colonel a country house of my father's, distant both from Lyme and Charmouth about a mile and a half, which (for the privacy of it) we determined should be the place whither his majesty, with the Lord Wilmot, who then waited upon him, should repair on Monday next, that I might then and there give his majesty a farther account of what had passed in the interim between myself and the master. And now being abundantly satisfied and exhilarated in the review of the happy progress we had thus far made, with most affectionate embraces the noble colonel and myself parted ; he returning to his house to wait upon his majesty, and myself towards mine, vigorously to prosecute what yet remained on my part to be done with the master, in order to the compleating of this work thus happily begun ; in the performance of which, that I might approve myself faithful, I the same day, and the day following, and also on the Monday after, having diligently sought out the master, moved and pressed him so earnestly to the punctual performance of his passed promise, that he seemed discontented at my importunity, as betraying in me a suspicion of his fidelity. A little to allay his passion, I told him I was assured that the gentleman, my friend, would be at Charmouth on Monday, and that if he were not ready to transport him, it might prove an undoing both to my friend and me. Whereupon, to vindicate himself, he told me that he had taken in his ballast, that he had victualled himself, and haled out his vessel to the cob's mouth, for fear of being beneaped, because the tides at that time were at the lowest. Being well satisfied with this answer, I left him (after that I had given him instructions how to prevent any jealousies that might arise in the breasts of the mariners concerning the persons to be transported), and immediately went to the aforesaid country house of my father's, whither when I was come (and perceived that I was the first comer), that I might also erect a blind before the tenant's eyes, I demanded of him whither the London carrier had passed that day or not ; telling him, withal, that I expected two or three friends, who promised to meet me there about the time of the carrier's passing that way. His answer to me was but little to the purpose ; but in half an hour after my arrival there, came the king, with Mrs Julian Coningsby, a kinswoman of the colonel's, who rode behind him, the Lord Wilmot, Colonel Wyndham, and his man Peters, attending on him. After their coming in, I took the first opportunity to acquaint his majesty with what had passed betwixt myself and the master after Colonel Wyndham's departure from me. The result of all which was this, that the master had assured me that all things were in a readiness for the intended voyage, and that (according to the instructions given him) he had possessed the seamen with a belief that one of the passengers viz. my Lord Wilmot was a merchant, by name Mr Payne ; and the other, meaning the king, was his servant. That the reason of Mr Payne's taking ship at Charmouth at such an unseasonable hour, and not at Lyme, was because that, being a town corporate, he feared an arrest, his factor in St Malo having broken him in his estate by his unfaithfulness to him ; and that therefore he was necessitated with this his servant speedily and privately to transport himself to St Malo aforesaid, in order to the recovery of such goods of his as by his said factor were detained from him ; the sending of which goods at several times this servant of his could sufficiently testify and prove. This I then rather acquainted his majesty and the Lord Wilmot with, that after their being shipped (the more to confirm the mariners), they might drop some discourses to this effect. His majesty having showed his approbation of what I had done, was graciously pleased, as a testimony of his royal favour (which I have ever esteemed as a jewel of greatest worth), to bestow upon me a piece of gold, telling me that at present he had nothing to bestow upon me but that small piece ; but that, if it ever should please God to restore him to his kingdoms, he would readily grant me whatsoever favour I might in reason petition him for. Upon this his majesty, attended as is before expressed, rode towards Charmouth, commanding me to hasten to Lyme, and there to continue my care that all things might be performed according to his majesty's expectations and the master's promise. Accordingly, I made haste home, found out the master, acquainted him that my friend was now at Charmouth, and that I newly came from him. He replied, that he was glad of it, that he would presently repair to Charmouth to speak with him, and to tell him when he would come ashore for him ; which accordingly he did. And thus far all things succeeded according to our best wishes, both the wind and tide seeming to be at strife which of them should most comply with our desires. But after all these fair hopes, and the great likelihood we had all conceived of his majesty's happy transportation, it pleased God Almighty, for the clearer manifestation of his infinitely glorious wisdom and powerful goodness in his majesty's preservation, suddenly to blast this design, and to cast his majesty upon new streights and dangers. For the master, either through weakness of judgment, or else in design to prevent a discovery, had utterly forborne to acquaint his wife with his intentions to go to sea, until it was almost time for him to go aboard. Whereupon he no sooner called for his chest, but his wife asked him why he would go to sea having no goods aboard. The master now thought himself necessitated to tell her Mr Ellesdon had provided him a fraught, which would be much more worth to him than if his ship were full loaden with goods, he being to transport a gentleman, a friend of his. His wife (having been at Lyme fair that day, and having heard the proclamation read, wherein £1000 was promised as a reward for the discovery of the king, and in which the danger of those also was represented that should conceal his majesty, or any of those that were engaged with him at Worcester, and apprehending that this gentleman might be one of the party) forthwith locked the doors upon him, and, by the help of her two daughters, kept him in by force, telling him that she and her children would not be undone for ever a landlord of them all ; and threatened him that, if he did but offer to stir out of doors, she would instantly go to Lyme, and give information both against him and his landlord to Captain Macy, who had then the command of a foot company there. Here the master showed his wisdom not a little by his peaceable behaviour ; for had he striven in the least, it is more than probable his majesty and his attendants had been suddenly seized upon in the inn. But I must needs awhile leave the master a prisoner in his own house, his wife and daughters being now become his keepers, whilst I render an account of the actings of Colonel Wyndham, who, with his man Peters, at the time appointed, went to the place agreed upon to expect the landing of the boat ; but no boat coming, after several hours waiting (because he saw the tide was spent), he resolves upon returning to the inn. In his way thither he discovers a man coming towards him, dogged at a small distance by two or three women. This, indeed, was the master of the vessel, who by this time had obtained liberty (yet still under the eyes of his over-jealous keepers) to walk towards the seaside, with an intention to make known to those that waited there for him the sad tidings of this unexpected disappointment, together with its causes. The colonel (when they met), though he conceived it might be the master, yet, being not certain of it, and seeing the women at his heels, passed him by without enquiring into the non-performance of his promise. Your lordship may easily guess that this frustration of hopes was matter of trouble as well as admiration to his majesty. The issue of it was that Peters, very early the Tuesday morning, was sent unto me to know the reason of it. He had no sooner delivered his message, but astonishment seized on me ; and the foresight of those sad consequences which I feared might be the fruits of this disaster, wrought in me such disquietment of mind, that (for the time) I think I scarcely sustained the like upon any occasion in all my life before, my confidence of his majesty's safe departure adding not a little to the weight of that load of sorrow, which afterwards lay so heavy upon me. The cause I plainly told him I was wholly ignorant of, except this were it, that in regard it was fair-day the master might not be able effectually to command his mariners out of the alehouses to their work, but promised speedily to search into it ; and upon after enquiry, I found it to be what I have before related. But here (because I apprehended that delays might prove inauspicious) I presently dismissed the messenger with this my humble advice to his majesty, that his longer stay in Charmouth might endanger his discovery ; which had certainly proved the issue of it, had not God, the King of kings, graciously, and even miraculously, prevented it. For the hostess of the house, little thinking what manner of guests the chambers before spoken of had been secured for, had at that time admitted to be her ostler one of Captain Macy's soldiers, a notorious knave ; who observing and taking notice that the colonel and his man went out so late at night towards the seaside, and that the rest of the company, during their absence, were more private than travellers are wont to be, and perhaps inspired and prompted by the devil, strongly suspected one of these guests to be the king, under the disguise of a woman's habit, and ceased not once and again to discover his jealousies unto his mistress. But she (though, from the fellow's words, and the consideration of some circumstances which that night and some days before had occurred, she had some thoughts that it might be so, yet) detesting as much to lodge treason in her heart, as she would have been proud of entertaining the king in her house, very passionately rebuked the ostler for these insolencies, hoping by that means to put a stop to his (as she judged) treasonable projects. Yet this her honest design wrought not the intended effect upon the heart of this her treacherous servant ; for the same morning, whilst Peters was with me at Lyme, he went to speak with the then Parson of Charmouth, intending to communicate his suspicions to him ; but found no opportunity to speak with him, he being at that time engaged in prayer with his family. Another remarkable passage we must of necessity here insert, which was this : My Lord Wilmot's horse wanting a shoe, in Peters's absence, the ostler led him to one Hammet's, a smith, then living in Charmouth, who, viewing the remaining shoes, said : " This horse hath but three shoes on, and they were set in three several counties, and one of them in Worcestershire ; " which speech of his fully confirmed the ostler in his former opinion. By this time Harry Peters, being returned from Lyme, and my Lord Wilmot's horse shod, upon the advertisement that was sent him, his majesty immediately departed towards Bridport, a town eastward of Charmouth, and about five miles distant from it. The ostler, now that the birds had taken their flight, began to spread his net. For going a second time to the parson, he fully discovered his thoughts to him, and withal told him what the smith had said concerning my Lord Wilmot's horse. The parson thereupon hastens to the inn, and salutes the hostess in this manner : " Why how now, Margaret you are a maid of honour now." " What mean you by that, Mr Parson quoth she. Said he, "Why Charles Stuart lay last night at your house, and kissed you at his departure ; so that now you can't but be a maid of honour." The woman began then to be very angry, and told him he was a scurvy- conditioned man to go about to bring her and her house into trouble. "But," said she, "if I thought it was the king, as you say it was, I would think the better of my lips all the days of my life ; and so, Mr Parson, get you out of my house, or else I'll get those shall kick you out." I have presented this discourse in the interlocutor's own words, by this means to make it more pleasant to your lordship. But, to return to the main intendment of this my narrative, I shall (before we come in our thoughts to attend his majesty in his journey eastwards) humbly beg of your lordship this favour, that your lordship would here be pleased seriously to admire with myself the goodness of Almighty God in infatuating this ostler, and the rest of his majesty's enemies in these parts. First of all, the parson (being not a little nettled at the rude and sharp language the hostess gave him), taking Hammet the smith along with him, he speedily applied himself to the next justice of the peace, to inform him of the fore mentioned jealousies, together with the reasons of them ; and earnestly pressed him to raise the county by his warrants, in order to his majesty's apprehension. But he (as God was pleased to order it), thinking it very unlikely that the king should be in these parts, notwithstanding all the parson's bawling and the strong probabilities upon which their conjectures seemed to be grounded, utterly rejected his council, fearing lest he should make himself ridiculous to all the country by such an undertaking. As for the ostler, his imprudent managing his mischievous intention discovered itself two ways ; first, in his having recourse to the parson ; whereas, with greater likelihood of success, he might have taken the advice and assistance of his fellow-soldiers, three whereof, being very desperate enemies to his majesty, were at that time inhabitants of Charmouth, and his nearest neighbours. In the next place, his egregious folly was further manifested in his delaying to acquaint his captain at Lyme with his suspicions abovenamed until twelve of the clock that day ; for had it not been for this neglect of his, his majesty's escape would have been (in reason's eye) impossible ; his captain, Macy, having no sooner received the report of these surmises, and information on what horses and in what equipage, and which way the persons suspected made their departure from Charmouth, but, having (in all likelihood) the promised reward of such mischievous diligence in his eye, he instantly resolves to leave no means unattempted, that with the least shadow of probability might conduce to his majesty's attachment. In pursuance of which resolves he presently mounts, and setting spurs to his horse, in a full career he rides towards Bridport, where, at his arrival, after a little enquiry made, he was given to understand that some persons, with whom the description he had received most exactly suited, had dined at the George that day, but not long before his coming were departed towards Dorchester. This, therefore, was the next place to which he posted (the wings of covetousness and ambition more nimbly transporting his mind than it was possible his horse could convey his body) ; which he no sooner entered, but (as if he had been to execute some warrant for the apprehending the most notorious felon in the kingdom, with the utmost haste and diligence imaginable, he searched all the inns and alehouses in the town. But God (who had given him no commission to violate majesty) was graciously pleased to make this furious hunter to overrun the game he hunted for. Wherefore dismissing him from creating any further trouble to your lordship (whose principles, I doubt, rather led him to the height of discontent at his supposed loss, than to a Christian observance of that divine hand of Providence which was so eminently seen in the preservation of that royal personage which he intended to make a prey of), let us now again return to his majesty : Who, in his passage from Charmouth, meeting with no interruption in his journey, soon reached Bridport ; and turning in at the George, he (to the astonishment, doubtless, both of himself and his attendants) found himself surrounded by his enemies ; there being at that time in the said town divers foot companies drawn together, who were designed for an expedition against Jersey. But being as yet unsuspected (lest he might too late bewail the sad effects of delay), after a short repast (too short, indeed, at any time but this, for so great and heroical a prince), his majesty left this town, going on the way that leads to Dorchester ; in which he had not rode past half a mile, ere by the finger of divine Providence he was directed into a narrow lane on the left hand of Dorchester road, by which means (though they knew not whither they went) they were that evening safely conducted to Broadwindsor, a country parish some six miles north of Bridport. They very fortunately lighted upon an inn where both the inn-holder and his wife were very well known to Colonel Wyndham, they having formerly been servants unto some of his allies. The colonel being confident he had an interest in them, upon the account of his former knowledge of them, and the relation they sometimes had to some of his kindred, persons of no mean quality, requested that he and his company might that night be lodged in the most convenient rooms for privacy their house would afford ; telling them, that himself and his brother, Colonel Bullen Reymes (meaning my Lord Wilmot, who very much resembled him), had transgressed their limits, the royalists at that time being confined within five miles distance from their homes. This they readily condescended to ; and thereupon led them into the uppermost chambers in their house. Yet here the face of danger was again discovered unto them ; for they had not been housed much above an hour before a company of troopers (to the number of forty) came thither, with an intention to quarter in this and other houses adjacent ; which accident might in all likelihood have proved fatal to his majesty (the soldiers everywhere about that time being proudly inquisitive into the names, qualities, affairs, and businesses of strangers), had not God in his infinite mercy incapacitated them for such like actings here, by cutting out work of another nature for them. For having a woman in their company, who not long after their coming thither fell in travail, and was delivered of a child, the officers and other inhabitants of the said parish, having notice thereof, contested so long with them about freeing their parish from the burthen of its maintenance, till sleep and drowsiness had rendered their heads unfit for anything but their pillows ; upon which, whilst they securely slept, his majesty, together with his attendants, arising some hours before day, and taking the opportunity of that time of silence, retired themselves undiscovered unto Trent. Where after his majesty had concealed himself about a week, he departed thence to one Mrs Hyde's, near Salisbury. What afterwards passed,must needs leave to others that had the honour to know it, being myself unable to spin the thread of this history any longer. Thus have I (right honourable), without the least violation of truth's chastity, made a brief collection of those never-to-be-forgotten miracles of Providence, wrought by the hand of Omnipotency for the conservation of his most serene majesty in the midst of the many perils he was exposed to in the west of Dorset, which came within my cognisance, which I humbly lay (such as it is) at your lordship's feet, being thereunto prompted upon the following considerations : First, that I might present your honour with some new matter for your meditations, having frequently observed your lordship to be much delighted both in moving, and also in hearing, discourses upon this subject. Secondly, that your lordship, by recounting in the hearing of others these Dei Magnalia, may quicken and excite them to a serious minding and due improvement of the infinite wisdom, power, and goodness of the most high God (the great preserver even of kings), manifested in what hath been the subject-matter of the precedent narrative. Lastly, that I might leave in your honour's hands some monument of my real gratitude for the many favours your lordship has been pleased to confer on me. But it is time for me to remember what the poet said to his Augustus : " In publica commoda peccem, Si longo sermoiie morer tua tempora." Lest, therefore, I should offend through my unseasonable prolixity, having first, with all submission, craved your lordship's pardon for this my great presumption in tendering to your lordship, whom the world justly esteems so absolute a master of speech, such a rude and unpolished story, I shall only beg the honour to subscribe myself,

My Lord, Your Lordship's Most humbly devoted Servant,

WILLIAM ELLESDON