|

St

James's Church |

Medieval

documents from the late 13th and early 14th centuries make it clear that the bishop's

palace extended from Abbeygate Street on the south to the passage separating it

from the King's Bath on the north, and from the rear of the tenements on Stall

Street on the west. These conclusions are reinforced by the early post-medieval

evidence. The eastern limits are not clear, except at the southern end, where

the Porter's Lodging was situated, but must obviously fall close to those shown

on fig. 3, based on post-medieval property lines. Within this neat near-rectangle

there was an obvious anomaly, only partially straightened by what appears to be

a rearrangement dating from the early 17th century, and still visible today. Number

2, Abbey Street and the present Crystal Palace public house occupy a plot that

is noticeably at an angle to the rest of the layout here, indeed to that of the

whole monastery. The only buildings that share this alignment are the now vanished

church of St Mary de Stalls, and - to a lesser extent - the cathedral itself.

Very limited excavations under both present buildings have revealed the existence

of a Christian burial ground, many of whose occupants displayed physical traits

common among the Anglo-Saxons.The propinquity of the bishop's chamber, the orientation,

and the presence of early burials points powerfully to this plot being exactly

that of St James's before 1279. That it was of Saxon origin is clear by its awkward

incorporation into the bishop's close. It was obviously already too well established

by 1091 to move, and had to be accommodated in the new plans.

|

The

Site of the Abbey Church

As to the position of the Saxon abbey, we can only

guess that it occupied a site somewhere within the later medieval precinct (fig.

1). Comparison with sites elsewhere, such as Wells or Winchester, might suggest

a location somewhere near, but not necessarily under the present building. Alternatively,

it is still possible that it may have stood eri the site of the modern abbey,

as is the case at Romsey, for example. Another intriguing possibility is that

the abbey church may be represented by the undoubtedly Saxon church of St James

that stood west of Abbey Green until 1279. In that year it was partly demolished

and converted into the bishop's private chapel, and the parishioners provided

with a church on a new site (the remains of which are buried underneath Woolworth's)

that served until the Blitz of 1942. But, of course, the dedication is against

this suggestion.

Only excavation now holds any hope for discovering the site

of the Saxon abbey. A few scraps of evidence in the form of burials suggest that

Saxon cemeteries existed immediately south of the

|

In

Bath the Saxon street plan was overlaid by the Norman cathedral priory and bishop's

palace, but can we diseern the pattern beneath (Illus, .?)? Alfred the Great was

apparently responsible for the recreation of Bnrli as n borough (Manco iyyS, 39-4.1).

Some of the city's medieval streets and lanes fit the pattern ot borough planning

in liis time. Cimliffc (i'jS4, 351-52} extrapolated trom those remnants to recreate

the original Saxon plan. He assumed that the main Saxon artery ran straight down

from tbe North Gate to a Saxon south gate on the site of the medieval Ham Gale.

The northern part of this street — I ligh Street — is still there. The

southernmost part was represented in the medieval period by a lane running south

from the Abbey Gate to the Ham Gate (Illus. i ami 2). However it is now clear

that the Saxon main street could not have run in a direct line between the two.

The Saxon cemetery ot H.ith Abbey blocked that route (liell iyij6, i 5). So presumably

the street swung westwards around li.iih Abbey, established long belore Allred.

It would have been convenient to adopt the new main street as the western boundary

ot the Saxon abbey and later of the Norman cathedral priory. Certainty the priory

boundary ran along the east side of the lane to the Ham (Sate, That is apparent

from the map of 1725 (Illus, i), which was made for the owner of the former priory

site. His property is shown in darker colours.

If the bishop's elose was laid

out on the other side of the street, that would explain its curious alignment.

It would have followed the street swinging westwards around the abbey. For the

bishop to lay out his close on a block between two pre-existing streets would

have simplified the planning process. It seems that part of the street swallowed

up by the close and priory continued to have a public use until i^yy. The close

had engulfed the Saxon Church ot St James. Successive bishops tolerated the incursion

of parishioners until in December 1279 Bishop Robert Hurnell madets tor a new

Church of St James to be built outside his close. The nave of old St James's was

to be convened into his private chapel. He gave the site of the chancel to the

priory, along with two other areas to enhrge the court and the priory gate. This

suggests that a strip of land was being thrown into the priory that wns no longer

needed by the parishioners of St James for access CO their church. Prior Walter

de Anno converted part of the extra ground into a laundry and built a cellarer's

room by the gate. Since he was much engaged with waterworks, lie may also have

been responsible for building the priory conduit house (Mnnco 1994, 80-81, 93-94

and fig. 4). All three features survived the I )jssoluiion to appear on SavileN

map (lllus. 2), by which lime they had become attached to gardens within the former

close. They form a line where one would c\pect the main Saxon street on the presumption

that the bishop's close used the street as its eastern bound.uy.

In summary,

the evidence indicates that the Norman bishop's close at li.itli was a roughly

rectangular block, probably laid out between two Saxon streets. To the east was

Hath Priory. Between the close and the priory precinct ran a way to the parochial

Church of St James, probably preserving pait of the line of the Saxon main street. |

|

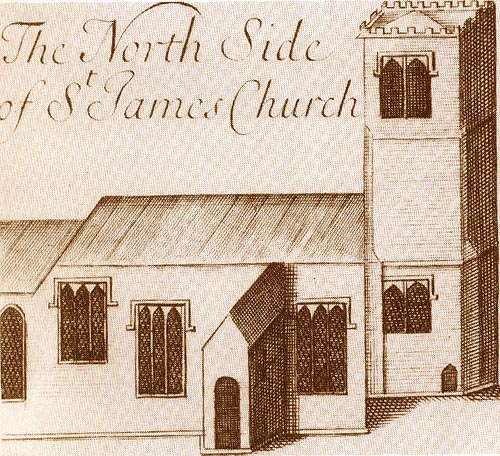

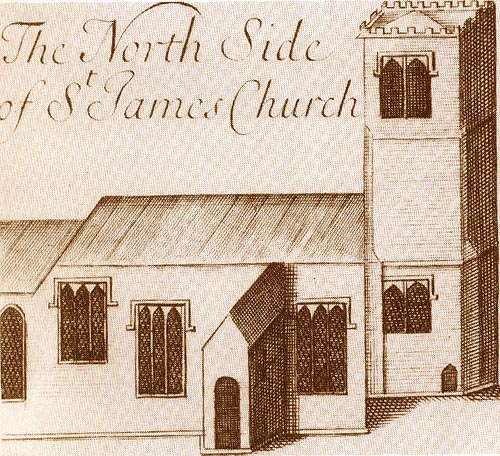

St James Church 1694 |

|

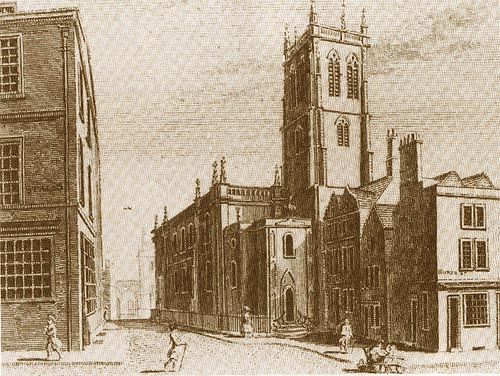

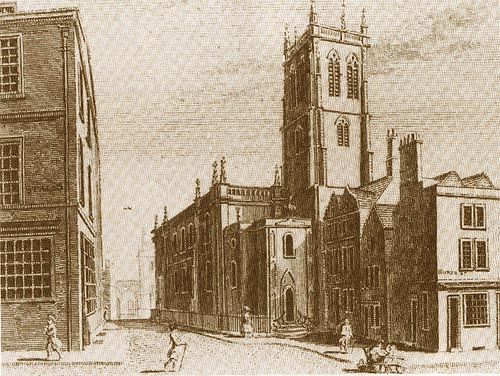

St James Church 1784 |

|

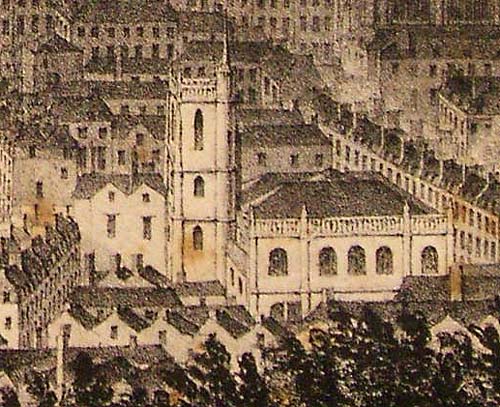

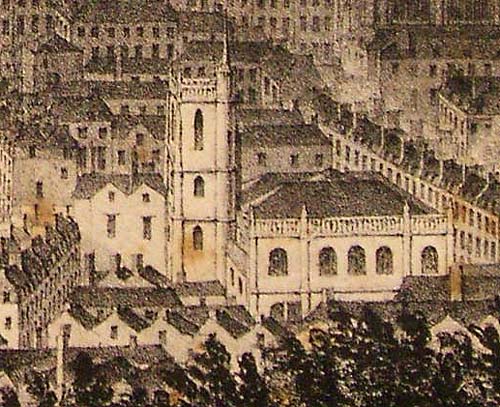

St James Church 1795 |

|

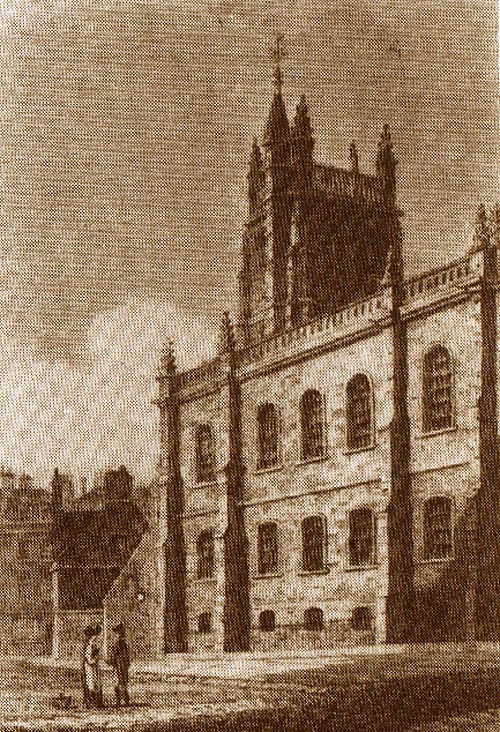

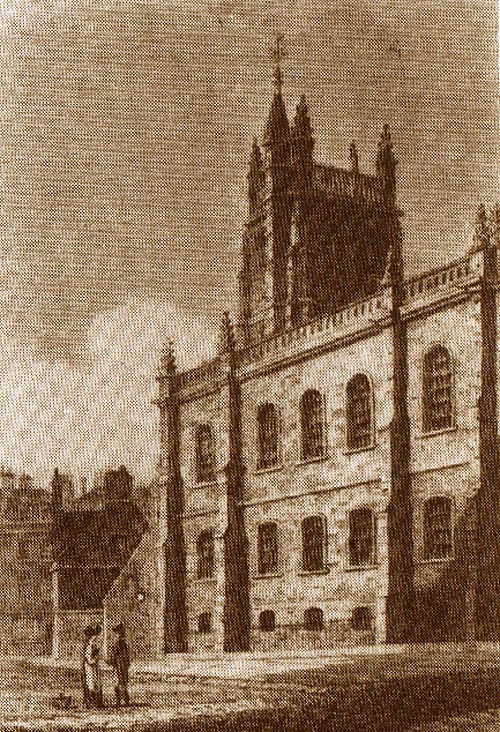

St

James Church 1818 |

|

St

James Church 1850 |

|

St

James Church 1900 |

| Mediaeval

church partially rebuilt, 1716. Nave rebuily (Thomas Jelly and John Plamer) 1768-9.

West end and tower replaced and nave rebuilt yet again (George Phillip Manners)

- 1848. Gutted by bombing 1942. Demolished in 1957 to make way for Woolworth`s

(now Boots the Chemist). |

| |

| |

| |

| |