.jpg)

Click on other links below to go to further information regarding this historic building and its history.

What we see today is in fact the third Structure. The first was a small chapel which would have stood further out to sea than where the Heritage Centre is today. For the original village was very small and according to the Domesday Book of 1086 had a working population of 30, of whom 16 were Salt Boilers. They would have cut down timber from the surrounding forest and light fires under lead basins filled with Sea Water and drain off the Salt, which was mainly used as a preservative. This practise went back to Roman Times and there is reference to a Salt House at neighbouring Lyme Regis owned by Sherborne Abbey in a Document in 774A.D. There is also a Grant in 1172A.D. by William Heron (Hayrun) to the Abbot of Forde of “all that part of his tenement in Charmouth (Cernemue) which lies to the west of the land of Henry de Tilli between the top of the brow of the cliff and the sea as far as the stream of Cerne and to the south of the curtilage formerly of Elfric up to the sea, for making salt, keeping a boat or other purposes”.

Charmouth was one of a number of villages that formed the “Hundred of Whitchurch Canonicorum” which was created by King Alfred in the 9th Century. Each village had its “Chapel of Ease” that served the Mother Church and came under the Diocese of Salisbury. Some of these Chapels have survived, often incorporated into a later larger building as at Wooton Fitzpaine and Pillesden. But to get an idea of how it would have looked in its day, one only has to walk along the cliffs to the remains of the Chapel at nearby Stanton St. Gabriel's, which has survived virtually intact, apart from its roof.

The earliest document so far found is “A Charter at Salisbury Cathedral”, dated 1240, which mentions the 'Capella de Cernemue,' i.e., the Chapel of Charmouth, when there is a dispute between William Heiron , Lord of Charmouth and the Parson of Church of St. Wite and Holy Cross (now Whitchurch Canonicorum). The settlement was in a precarious state with its position so near the Sea and this can clearly be seen by an entry in the ancient Cartulary kept at Forde Abbey today which has a record from the year 1281, which relates to this as follows:

“Notification by Robert [Wickhampton], Bishop of Salisbury, that he has been informed by many trustworthy men that the secular chapel of Charmouth (Cernemue), built a long time ago near the sea, has been ruined by the battering of the sea and storms. He gives his authority and assent to the Abbot and monks of Forde, the postulant patrons of the chapel, to move it to a more suitable site than the shore and build a chapel on their own land to the honour of the blessed apostle Matthew and All Saints, in which they may provide clerics and secular priests to minister divine service with due devotion”.

It would seem that from at least 1170, when Richard del Estre gave land to the Monks that they were to build a Grange and other buildings. In 1297, William, the Abbot decided to improve the Manor and create a Free Borough. This was based along the Street, which even today has the vestiges of this, with its Stone boundary wall to the north and long burgage plots stretching towards it. The document confirms the position of the former Chapel when it describes a boundary as “from there along the course of the river to the sea and to the chapel of the vil”. There is also a document of the same year witnessed by Dom Stephen, parson of Charmouth and Seaborough

The creation of the borough must have coincided with the need for a new church and this was to be built near the centre where the Street was bisected with the tracks that lead inland to Wootton and to the beach. The borough whose boundaries are so well described in the Cartulary was never very successful, with its competition from nearby Lyme Regis and Bridport. In time the original plots were amalgamated into large more viable holdings. A survey of 1564 shows most families renting an acre behind their property on the Street and a further acre of common land in the fields between it and the coast.

The new Church served an increased population, and according to Hutchins was improved at the beginning of the 16th century after a bequest was given for this. This would coincide with the time when Thomas Chard was Abbot of Forde and seemed intent on spending its wealth, before being seized by King Henry VIII. He is known to have rebuilt what is today known as “The Abbots House” for his brother who was Steward. His initials, T.C., can still be seen today above a blocked up doorway. He also initiated the construction of the building that is now “The Manor House” opposite the Church, whose roof timbers are dated to the 16th century. We are fortunate that a memorial to his work on the village church which has survived in a statue of an Abbot, no doubt representing Thomas Chard. This was originally on the apex of the rear of the old church and was later found in two parts built into the walls of Little Hurst and The Rectory.

A number of Rectors are recorded as serving the Village from Stephen in 1315 up to Stephen Skinner to date. Many of whom have interesting biographies. The most startling fact looking at the dates is how just three fathers and their sons were in office for so many years. These were the Norringtons(1596-1646), Bragges ( 1673-1747), Coombes( 1747-1818). The latter was William Coombe who was Rector of both this village and adjoining Catherston. His son, Brian succeeded him as Rector of Catherston. Although he was only Curate of Charmouth, he deputised for the Rector, John Audain, who spent most of his time as a Privateer in the West Indies.

After the reformation in 1539, when Charmouth became a member of the Diocese of Bristol, it was to have a series of “Lords of the Manor”, who were also Patrons of the Church. The most famous of these was William Ellesdon who lived in the Manor House opposite and was instrumental in the attempt to assist King Charles II and escape to France from Charmouth. A boat was to meet him on the beach at night. But the owner, Stephen Limbry was prevented by his wife, who getting wind of it, locked him in their house, and the attempt had to be abandoned. There is a link to this event with a 17th century Stone Tomb near the entrance to the Church for John Limbry and his daughter Margaret who were related. Another connection with this event was that the Parson at the time was Bartholomew Wesley, great grandfather of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church. He was so busy with his prayers that evening, that he was too late to report the incident and assist the Kings capture. William Ellesdon`s son, Anthony, was to live in Charmouth at the Manor for almost eighty years and his life is commemorated in a magnificent marble memorial by the Altar.

As the population of the village expanded, more seating was required and a Gallery was built to accommodate them. When this still was not enough by 1835, it was proposed to enlarge the building with an aisle on the northern side. Mr. Charles Wallis of Dorchester, an architect was instructed to carry out a survey of the ancient structure and reported that “he had never seen so dilapidated or unsafe a building and that it was necessary to build a new church”. The whole village worked with enormous energy to raise the money. The numbers of residents, who subscribed, was 334 whose subscriptions came to £1221.The number of friends outside the parish was 375 whose donations came to £1130 making a total of £2351. The final cost came to £3098, the balance coming from grants and sale of material from the demolition.

But what did the old Church look like? It was too early for photographs.I have not been able to find any illustrations apart from a curious watercolour from 1828, painted by Diana Sperling taken from her bedroom window at the Rectory behind the Church. It shows a section of the rear of the building covered with a thick layer of ivy. But most interesting is that the roof is surmounted by the stone cross of the Abbot that has survived today.Another engraving from 1820 shows the village from Old Lyme Hill and the church dominating the village. After standing for over 500 years it would be tragic to think that there is no reasonable represenation. But thanks to the foresight of William Hoare, a village Carpenter we know exactly all we wish about it. He constructed the most amazingly accurate model, which by a miracle has survived and is now housed in the Pavey Room at The Elms. You can even take the roof off it and see all the Church furniture, memorials and boxed pews. Although it covered approximately the same ground area as the present church, its roof height was much lower and it’s Tower taller.

The Architect chosen to design the new Church was Charles Fowler, whose mother, Jane had lived with her sister Lucy, wife of Samuel Coade Culverwell at Little Hurst, which is now the Doctor`s Surgery. We can still see her marble memorial high above the Vestry door. The earlier architect, Charles Wallis, who had surveyed the Church originally was far from happy about the choice and made his feelings very clear in an objectionable letter to the Church Wardens. But we were very lucky to have had such a famous architect. Today his main claim to fame is the Covent Garden Piazza, but it only one of many famous buildings he designed. You just have to go to Honiton to see the church he designed in the town centre and to Exeter to see its Market.

There is a wonderful record of St. Andrews, as it was renamed, by Thomas Galpin Carter, soon after construction. It is a coloured engraving that hangs in the north Aisle that depicts a group of villagers standing by James Warden Tomb.

Again, miraculously the original plans and correspondence for the construction has survived and it is almost a “do it yourself” of how to build a church. They are all beautifully drawn and the letters give an insight into Fowlers approach, with its emphasis on preservation of many features from the earlier building which were to be incorporated into the new one. It would seem that all the earlier memorials were included and the grave yard remain undisturbed. Although the builders were from Bridport, Samuel Dunn from Charmouth was chosen as Officer of Works and it was his son in law William Hoare, who was to produce the lasting memorial to the former building with his magnificent model.

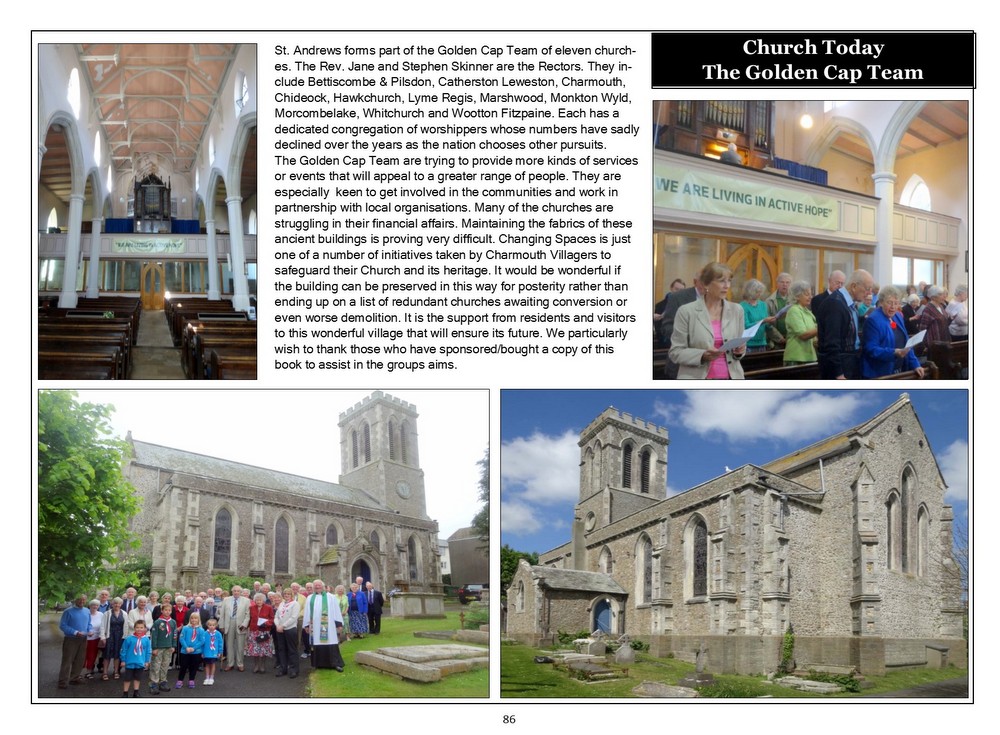

It is sad reflection on life today that such a fine building is not appreciated more, for within its walls is much of Charmouth`s rich heritage. But there is a movement in the form of a group called Changing Spaces to improve villager’s awareness of it and improve its facilities. Click on Changing Spaces Link to find out more.

Year |

Rector |

Year |

Rector |

Year |

Rector |

Year |

Rector |

| 1332 | Richard de la Hegh | 1439 | Richard Piper | 1662 | Timothy Hallet | 1883 | William W Nicholls |

| 1335 | Reyner de Colonn | 1441 | John North | 1664 | William Lock | 1900 | Spencer E Simms |

| 1337 | Robert Warrener | 1464 | Thomas Newton | 1673 | Joseph Bragge | 1920 | Sidney Selwyn |

| 1349 | Robert Nightyngale | 1465 | Thomas Dyer | 1708 | Edward Bragge | 1922 | Fredrick E Markby |

| 1349 | William Corselin | 1465 | Thomas Fitz | 1747 | William Coombe | 1928 | Norman R. Bennet |

| 1362 | William Tolefate | 1534 | Edward Cambrook | 1783 | John Audain | 1933 | Claude D Ovens |

| 1364 | William de Fordington | 1544 | William Sankey | 1827 | William L Glover | 1945 | Edward J Mackie |

| 1382 | William Wotham | 1560 | Lawrence Orchard | 1833 | John Dixon Hales | 1963 | Harold Hacking |

| 1382 | William Langerigg | 1565 | John Evans | 1839 | James W Hatherell | 1969 | Robert H. T. Lucas |

| 1392 | William Launce | 1572 | George Estmond | 1843 | Edward R Breton | 1987 | John H Potter |

| 1435 | John Thredor | 1599 | Samuel Norrington | 1875 | Horace Moule | 1992 | Roger H Blankley |

| 1439 | Thomas Thorner | 1640 | Bartholomew Wesley | 1879 | John S Stewart | 1998 | Golden Cap Team |

Patrons |

Years |

Rector |

| Abott of Forde Abbey | 1280 - 1539 | |

| Queen Elizabeth I | ||

| Petre Family? | ||

| Pole Family? | ||

| Ellesdon Family ? | Bragge | |

| Richard Henvill of Bristol | 1747-1783 | Combe |

| Francis Phipps Henvill | 1783- 1827 | Audain |

| Issac Cooke of Bristol | 1827 - 1833 | Glover |

| Issac Cooke of Bristol | 1833 -1839 | Hales |

| Abraham Hatherell of Cheltenham | 1839-1843 | Hatherall |

| William Baylis of Charlton Kings, Glos. | 1843- | Breton |

| Rev. Thomas Hope of Warwick | Breton | |

| John Timswell Addams of Cheltenham | Breton |

-001.jpg)

.jpg)